摘要

本文部分内容来源于网络,个人收集整理,请勿传播

- Python的特殊之处在于Python有一把GIL锁,这把锁限制了同一时间内一个进程只能有一个线程能使用cpu,但是GIL并不是python只有的特性。

写在前面的概念

进程

程序并不能单独运行,只有将程序装载到内存中,系统为它分配资源才能运行,而这种执行的程序就称之为进程。

程序和进程的区别就在于:程序是指令的集合,它是进程运行的静态描述文本;进程是程序的一次执行活动,属于动态概念。

我们电脑的应用程序,都是进程,假设我们用的电脑是单核的,cpu同时只能执行一个进程。当程序处于I/O阻塞的时候,CPU如果和程序一起等待,那就太浪费了,cpu会去执行其他的程序,此时就涉及到切换,切换前要保存上一个程序运行的状态,才能恢复,所以就需要有个东西来记录这个东西,就可以引出进程的概念了。

进程就是一个程序在一个数据集上的一次动态执行过程。进程由程序,数据集,进程控制块三部分组成。程序用来描述进程哪些功能以及如何完成;数据集是程序执行过程中所使用的资源;进程控制块用来保存程序运行的状态

在多道编程中,我们允许多个程序同时加载到内存中,在操作系统的调度下,可以实现并发地执行。这是这样的设计,大大提高了CPU的利用率。进程的出现让每个用户感觉到自己独享CPU,因此,进程就是为了在CPU上实现多道编程而提出的。

有了进程为什么还要线程?

进程有很多优点,它提供了多道编程,让我们感觉我们每个人都拥有自己的CPU和其他资源,可以提高计算机的利用率。很多人就不理解了,既然进程这么优秀,为什么还要线程呢?其实,仔细观察就会发现进程还是有很多缺陷的,主要体现在两点上:

进程只能在一个时间干一件事,如果想同时干两件事或多件事,进程就无能为力了。

进程在执行的过程中如果阻塞,例如等待输入,整个进程就会挂起,即使进程中有些工作不依赖于输入的数据,也将无法执行。

例如,我们在使用qq聊天, qq做为一个独立进程如果同一时间只能干一件事,那他如何实现在同一时刻 即能监听键盘输入、又能监听其它人给你发的消息、同时还能把别人发的消息显示在屏幕上呢?你会说,操作系统不是有分时么?但我的亲,分时是指在不同进程间的分时呀, 即操作系统处理一会你的qq任务,又切换到word文档任务上了,每个cpu时间片分给你的qq程序时,你的qq还是只能同时干一件事呀。

再直白一点, 一个操作系统就像是一个工厂,工厂里面有很多个生产车间,不同的车间生产不同的产品,每个车间就相当于一个进程,且你的工厂又穷,供电不足,同一时间只能给一个车间供电,为了能让所有车间都能同时生产,你的工厂的电工只能给不同的车间分时供电,但是轮到你的qq车间时,发现只有一个干活的工人,结果生产效率极低,为了解决这个问题,应该怎么办呢?。。。。没错,你肯定想到了,就是多加几个工人,让几个人工人并行工作,这每个工人,就是线程!

线程

一个进程中可以开多个线程,为什么要有进程,而不做成线程呢?因为一个程序中,线程共享一套数据,如果都做成进程,每个进程独占一块内存,那这套数据就要复制好几份给每个程序,不合理,所以有了线程。

线程又叫轻量级进程,是一个基本的cpu执行单元,也是程序执行过程中的最小单元。一个进程最少也会有一个主线程,在主线程中通过threading模块,在开子线程

进程线程的关系和区别

关系

- 一个线程只能属于一个进程,而一个进程可以有多个线程,但至少有一个线程

- 资源分配给进程,进程是程序的主体,同一进程的所有线程共享该进程的所有资源

- cpu分配给线程,即真正在cpu上运行的是线程

- 线程是最小的执行单元,进程是最小的资源管理单元

- 同一个进程里的线程是共享同一块内存空间的

区别

进程和线程速度没有可比性,进程是资源集合,线程是执行单位;如果这么问,就是问两个线程那个快,实际是一样的

同一个进程的线程共享内存空间;进程内存是独立的

- 同一个进程的线程之间可以数据交互;两个进程想通信,必须通过一个中间代理来实现

- 创建新的线程容易,创建新的进程需要对其父进程进行一次克隆

- 一个线程可以控制和操作同一进程里的其他线程;进程只能操作子进程

什么时候用多线程

- python的多线程实际上是假的

- io操作不占用cpu

- 计算占用cpu 1+1

- python 的多线程不适合cpu密集操作型的任务,适合io操作密集型的任务

threading模块

这个模块的功能就是创建新的线程,有两种创建线程的方法:

直接创建

1 | import threading |

上面的代码就是在主线程中创建了一个子线程

运行结果是:先打印>>>>>>>>>>>>>2,在打印ending,然后等待3秒后打印thread 1

通过继承类创建线程

1 | import threading |

join()方法

这个方法的作用是:在子线程完成运行之前,这个子线程的父线程将一直等待子线程运行完再运行

1 | import threading |

setDaemon()方法

这个方法的作用是把线程声明为守护线程,必须在start()方法调用之前设置。

默认情况下,主线程运行完会检查子线程是否完成,如果未完成,那么主线程会等待子线程完成后再退出。但是如果主线程完成后不用管子线程是否运行完都退出,就要设置setDaemon(True)

1 | import threading |

主线程默认是非守护线程,子线程都是继承的主线程,所以默认也都是非守护线程

其他方法

- isAlive(): 返回线程是否处于活动中

- getName(): 返回线程名

- setName(): 设置线程名

- threading.current_Thread():返回当前的线程变量

- threading.enumerate():返回一个包含正在运行的线程的列表

- threading.active_Count():返回正在运行的线程数量

GIL全局解释器锁

无论你启多少个线程,你有多少个cpu, Python在执行的时候会淡定的在同一时刻只允许一个线程运行

首先需要明确的一点是GIL并不是Python的特性,它是在实现Python解析器(CPython)时所引入的一个概念。就好比C++是一套语言(语法)标准,但是可以用不同的编译器来编译成可执行代码。有名的编译器例如GCC,INTEL C++,Visual C++等。Python也一样,同样一段代码可以通过CPython,PyPy,Psyco等不同的Python执行环境来执行。像其中的JPython就没有GIL。然而因为CPython是大部分环境下默认的Python执行环境。所以在很多人的概念里CPython就是Python,也就想当然的把GIL归结为Python语言的缺陷。所以这里要先明确一点:GIL并不是Python的特性,Python完全可以不依赖于GIL

这篇文章透彻的剖析了GIL对python多线程的影响,强烈推荐看一下:http://www.dabeaz.com/python/UnderstandingGIL.pdf

线程锁(互斥锁Mutex)

一个进程下可以启动多个线程,多个线程共享父进程的内存空间,也就意味着每个线程可以访问同一份数据,此时,如果2个线程同时要修改同一份数据,会出现什么状况?

1 | import time |

正常来讲,这个num结果应该是0, 但在python 2.7上多运行几次,会发现,最后打印出来的num结果不总是0,为什么每次运行的结果不一样呢? 哈,很简单,假设你有A,B两个线程,此时都 要对num 进行减1操作, 由于2个线程是并发同时运行的,所以2个线程很有可能同时拿走了num=100这个初始变量交给cpu去运算,当A线程去处完的结果是99,但此时B线程运算完的结果也是99,两个线程同时CPU运算的结果再赋值给num变量后,结果就都是99。那怎么办呢? 很简单,每个线程在要修改公共数据时,为了避免自己在还没改完的时候别人也来修改此数据,可以给这个数据加一把锁, 这样其它线程想修改此数据时就必须等待你修改完毕并把锁释放掉后才能再访问此数据。

*注:不要在3.x上运行,不知为什么,3.x上的结果总是正确的,可能是自动加了锁

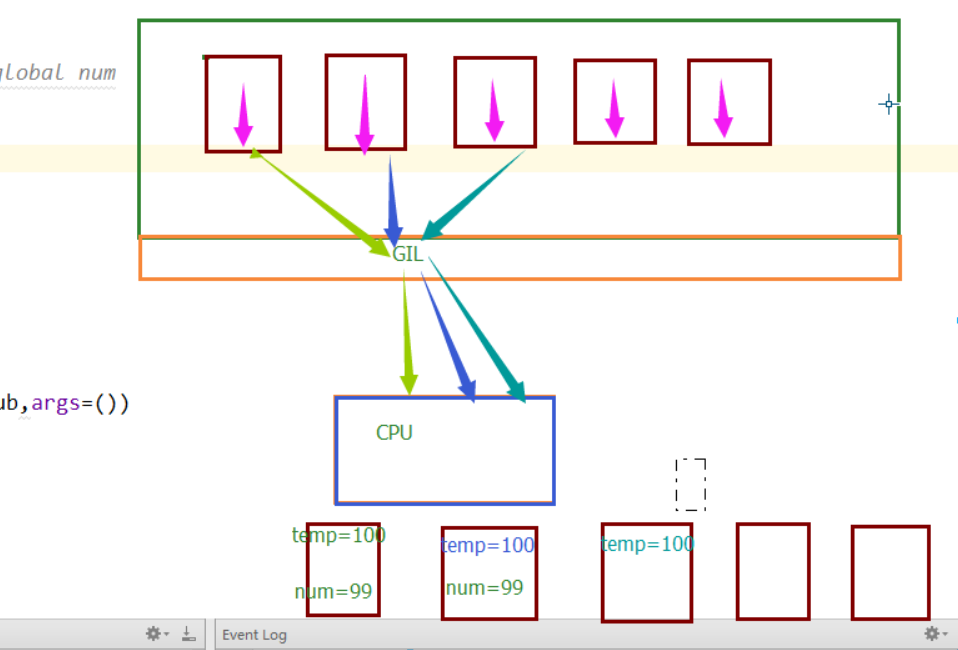

首次定义一个全局变量num=100,然后开辟了100个子线程,但是Python的那把GIL锁限制了同一时刻只能有一个线程使用cpu,所以这100个线程是处于抢这把锁的状态,谁抢到了,谁就可以运行自己的代码。在最开始的情况下,每个线程抢到cpu,马上执行了对全局变量减一的操作,所以不会出现问题。但是我们改动后,在全局变量减一之前,让他睡了0.1秒,程序睡着了,cpu可不能一直等着这个线程,当这个线程处于I/O阻塞的时候,其他线程就又可以抢cpu了,所以其他线程抢到了,开始执行代码,要知道0.1秒对于cpu的运行来说已经很长时间了,这段时间足够让第一个线程还没睡醒的时候,其他线程都抢到过cpu一次了。他们拿到的num都是100,等他们醒来后,执行的操作都是100-1,所以最后结果是99.同样的道理,如果睡的时间短一点,变成0.001,可能情况就是当第91个线程第一次抢到cpu的时候,第一个线程已经睡醒了,并修改了全局变量。所以这第91个线程拿到的全局变量就是99,然后第二个第三个线程陆续醒过来,分别修改了全局变量,所以最后结果就是一个不可知的数了。一张图看懂这个过程

加锁版本

1 | import time |

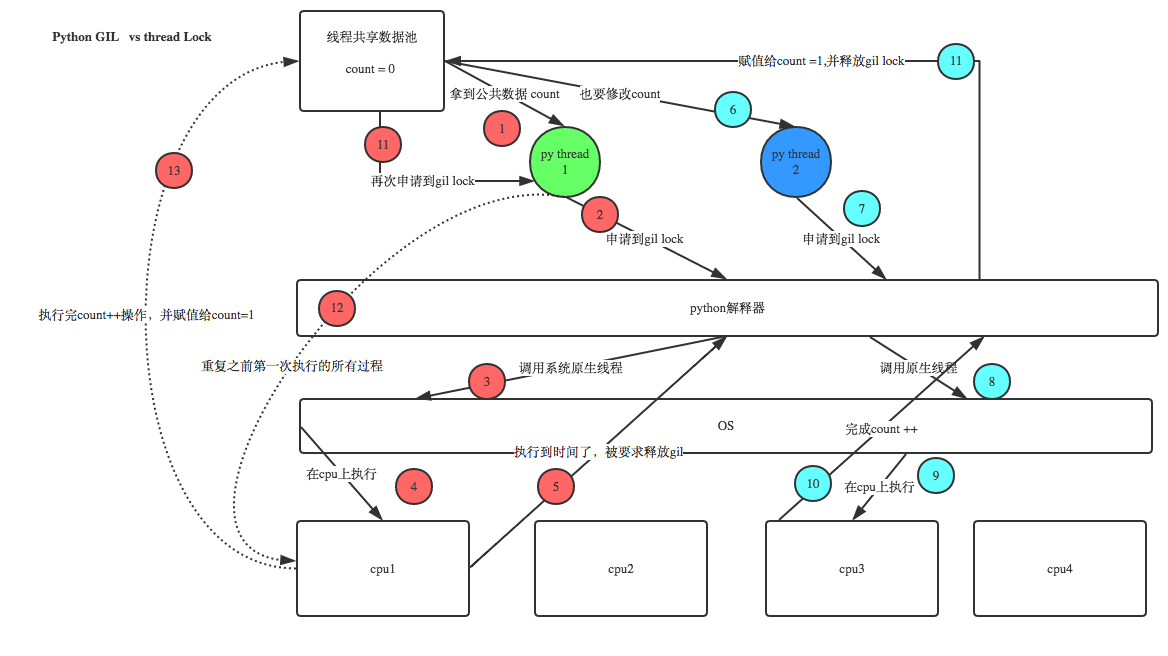

GIL VS Lock

机智的同学可能会问到这个问题,就是既然你之前说过了,Python已经有一个GIL来保证同一时间只能有一个线程来执行了,为什么这里还需要lock? 注意啦,这里的lock是用户级的lock,跟那个GIL没关系 ,具体我们通过下图来看一下+配合我现场讲给大家,就明白了。

那你又问了, 既然用户程序已经自己有锁了,那为什么C python还需要GIL呢?加入GIL主要的原因是为了降低程序的开发的复杂度,比如现在的你写python不需要关心内存回收的问题,因为Python解释器帮你自动定期进行内存回收,你可以理解为python解释器里有一个独立的线程,每过一段时间它起wake up做一次全局轮询看看哪些内存数据是可以被清空的,此时你自己的程序 里的线程和 py解释器自己的线程是并发运行的,假设你的线程删除了一个变量,py解释器的垃圾回收线程在清空这个变量的过程中的clearing时刻,可能一个其它线程正好又重新给这个还没来及得清空的内存空间赋值了,结果就有可能新赋值的数据被删除了,为了解决类似的问题,python解释器简单粗暴的加了锁,即当一个线程运行时,其它人都不能动,这样就解决了上述的问题, 这可以说是Python早期版本的遗留问题。

RLock(递归锁)

说白了就是在一个大锁中还要再包含子锁

1 | import threading,time |

Semaphore(信号量)

互斥锁 同时只允许一个线程更改数据,而Semaphore是同时允许一定数量的线程更改数据 ,比如厕所有3个坑,那最多只允许3个人上厕所,后面的人只能等里面有人出来了才能再进去。

1 | import threading,time |

Timer

这个类表示应该在经过一定时间之后才运行的操作。

计时器的启动方式与线程一样,通过调用它们的start()方法。通过调用thecancel()方法,计时器可以被停止(在它的动作开始之前)。在执行其操作之前,计时器将等待的间隔可能与用户指定的间隔不完全相同。

1 | def hello(): |

Events

- 可以用来设置标志位来让两个线程进行交互

- 一个线程操作标志位

- 另一些线程查看标志位

1 | import threading,time |

这里还有一个event使用的例子,员工进公司门要刷卡, 我们这里设置一个线程是“门”, 再设置几个线程为“员工”,员工看到门没打开,就刷卡,刷完卡,门开了,员工就可以通过。

1 | #_*_coding:utf-8_*_ |

queue队列

- 程序解耦

- 提高效率

- 相对于列表,队列的数据取走就没了。。。

- class queue.Queue(maxsize=0) #先入先出

- class queue.LifoQueue(maxsize=0) #last in fisrt out

- class queue.PriorityQueue(maxsize=0) #存储数据时可设置优先级的队列

- python2 : Queue;python3 : queue

1 | Queue.qsize() # 队列大小 |

生产者消费者模型

在并发编程中使用生产者和消费者模式能够解决绝大多数并发问题。该模式通过平衡生产线程和消费线程的工作能力来提高程序的整体处理数据的速度。

为什么要使用生产者和消费者模式

在线程世界里,生产者就是生产数据的线程,消费者就是消费数据的线程。在多线程开发当中,如果生产者处理速度很快,而消费者处理速度很慢,那么生产者就必须等待消费者处理完,才能继续生产数据。同样的道理,如果消费者的处理能力大于生产者,那么消费者就必须等待生产者。为了解决这个问题于是引入了生产者和消费者模式。

什么是生产者消费者模式

生产者消费者模式是通过一个容器来解决生产者和消费者的强耦合问题。生产者和消费者彼此之间不直接通讯,而通过阻塞队列来进行通讯,所以生产者生产完数据之后不用等待消费者处理,直接扔给阻塞队列,消费者不找生产者要数据,而是直接从阻塞队列里取,阻塞队列就相当于一个缓冲区,平衡了生产者和消费者的处理能力。

1 | import threading |

1 | import time,random |

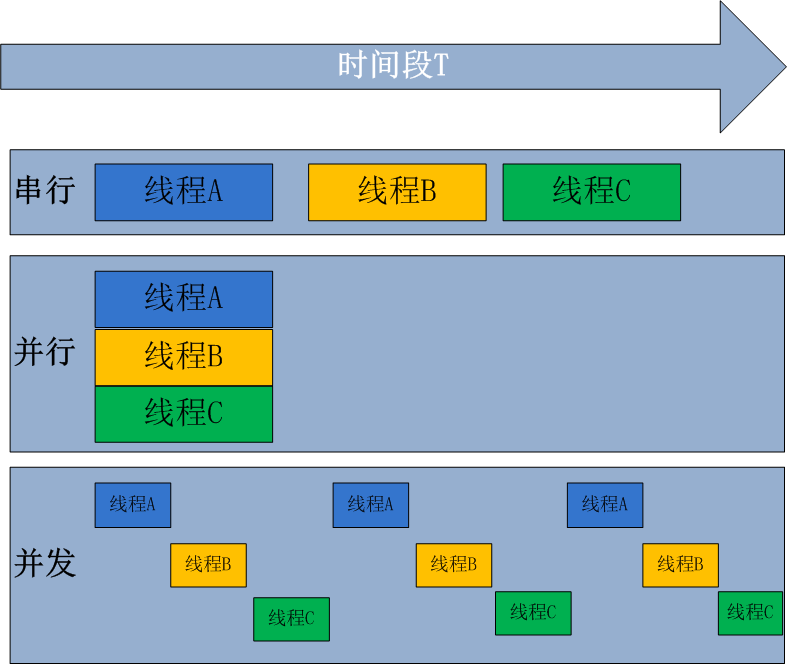

并行和并发

并行处理是指计算机系统中能同时执行两个或多个任务的计算方法,并行处理可同时工作于同一程序的不同方面

并发处理是同一时间段内有几个程序都在一个cpu中处于运行状态,但任一时刻只有一个程序在cpu上运行。

并发的重点在于有处理多个任务的能力,不一定要同时;而并行的重点在于就是有同时处理多个任务的能力。并行是并发的子集

以上所说的是相对于所有语言来说的,Python的特殊之处在于Python有一把GIL锁,这把锁限制了同一时间内一个进程只能有一个线程能使用cpu.

多进程multiprocessing

1 | from multiprocessing import Process |

1 | from multiprocessing import Process |

进程间通讯

不同进程间内存是不共享的,要想实现两个进程间的数据交换,可以用以下方法:

Queues

使用方法跟threading里的queue差不多

- 父进程克隆了一份q传给子进程

- 实际上就是变成了两个q

- 然后通过中间翻译的序列化数据让两个q共享数据

1 | from multiprocessing import Process, Queue |

Pipes管道

The Pipe() function returns a pair of connection objects connected by a pipe which by default is duplex (two-way). For example:

1 | from multiprocessing import Process, Pipe |

Managers

A manager object returned by Manager() controls a server process which holds Python objects and allows other processes to manipulate them using proxies.

A manager returned by Manager() will support types list, dict, Namespace, Lock, RLock, Semaphore, BoundedSemaphore, Condition, Event, Barrier, Queue, Value and Array. For example

1 | from multiprocessing import Process, Manager |

进程同步

Without using the lock output from the different processes is liable to get all mixed up.

- 进程虽然每个都是独立的

- 进程的锁存在的意义是比如打印到屏幕的时候不让输出乱到一起

1 | from multiprocessing import Process, Lock |

进程池

进程池内部维护一个进程序列,当使用时,则去进程池中获取一个进程,如果进程池序列中没有可供使用的进进程,那么程序就会等待,直到进程池中有可用进程为止。

- 同一时间有多少个进程在工作

- windows要import freeze_support 好像不加也行 用ifmain

进程池中有两个方法:

- apply 串行

- apply_async 并行

- callback 回调,执行完之后再调用

1 | from multiprocessing import Process,Pool |